Published right after the war in 1945, this book is a first edition featuring the artist’s personal narratives in Polish text, interwoven with thirteen graphic illustrations depicting the artist’s experiences in the labor camp Gross-Rosen. Administrcji "Hasła Ogrodniczo-Rolniczego,” 1945) Haas, alongside artists Ferdinand Bloch, Otto Unger, and Bedrich Fritta, secretly documented life in the camp while working for the Nazis’ graphic department in Terezin.Īntoni Gładysz, Powrót z Piekła Hitlerowskiego: Wspomnienie z Obozu Koncentracyjnego w Gross-Rosen i Litomierzycach (Tarnów: Nakł. The lithographs are 19" x 13.5”, with text in English, French, Czech, and Russian accompanying the graphic work. This set of twelve folio-sized lithographs was published in 1947, two years after Leo Haas’ liberation from the camp Ebensee.

Leo Haas, 12 Původních Litografií z Německých Koncentračních Táborů (Praze: Vydal Svaz Ozvobozených Politických Vězňů a Pozůstalých Po Politických Vězních, 1947) The woodcuts are a culmination of artistic exploration by the artist, Synek, and author, Václav Fiala, who were both interned in concentration camps for their participation in anti-Nazi resistance.

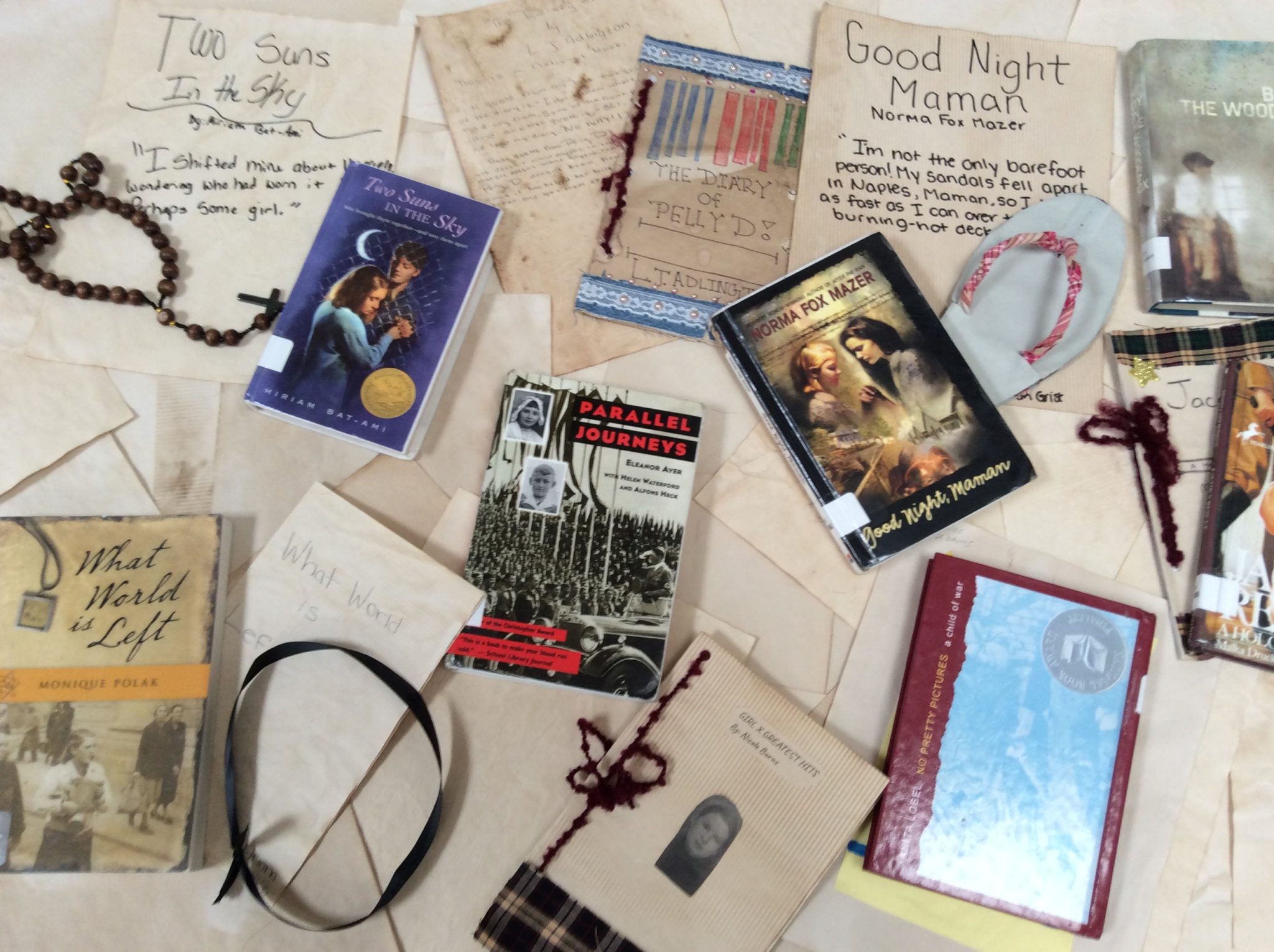

Holocaust project title ideas free#

This edition also includes an additional woodcut on the front free end paper, plate listing, text introduction, and publisher’s blank tissue dustwrapper. This incredible folio-sized portfolio features eight woodcuts of the concentration camps, each hand-signed by the artist, Václav Synek. Václav Synek, 1943: Osm Dřevorytů z Německých Věznic (Kutná Hora: Okresní kulturně-propagační komise KSČ v Kutné Hoře, 1947) However, researching artists from Theresienstadt brought my own family history into focus and deepened my appreciation for Watson Library’s commitment to building the Artists of the Holocaust collection.īelow is a selection of publications which we have recently required. In fact, a vibrant artistic culture existed despite the horrific reality of the camp, and the largest collection of Holocaust art can be traced back to Theresienstadt.Īlthough I am Jewish and have worked closely with Holocaust survivors before, I used to think that I had a relatively distant relationship to the atrocities of World War II.

Many Theresienstadt prisoners were artists, musicians, and intellectuals. During this process, I learned that my family had relatives in the Nazi Theresienstadt Ghetto, in the former military fortress town of Terezín. Sometimes emotion overcame me while I was reading about an artist or flipping through the pages of a new acquisition.

Working within this scope, I helped to expand the already significant collection using a multi-step research process. The now expansive collection covers three broad categories: art from the internment camps published as post-war portfolios retrospective books on art in the Holocaust from the 1940s to the present and finally, Holocaust publications by artists who were not interned, including war artists. These books give voice to artists whose work and story had been otherwise ignored, forgotten, or erased. Watson Chief Librarian, and Holly Phillips, collections manager for acquisitions, began enhancing our holdings of artists of the Holocaust. Moreover, I was excited to be working on an ambitious and important initiative called the Artists of the Holocaust project. I felt fortunate to find myself among passionate leaders and mentors at Watson Library. Watson Library staff as an Adrienne Arsht intern, excited to begin a career in librarianship.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)